Popular Keywords

- About Us

-

Research Report

Research Directory

Semiconductors

LED

Consumer Electronics

Emerging Technologies

- Selected Topics

- Membership

- Price Trends

- Press Center

- News

- Events

- Contact Us

- AI Agent

About TrendForce News

TrendForce News operates independently from our research team, curating key semiconductor and tech updates to support timely, informed decisions.

- Home

- News

[News] Breaking the Memory Wall: HBM Basics and the Rise of HBM4 in AI

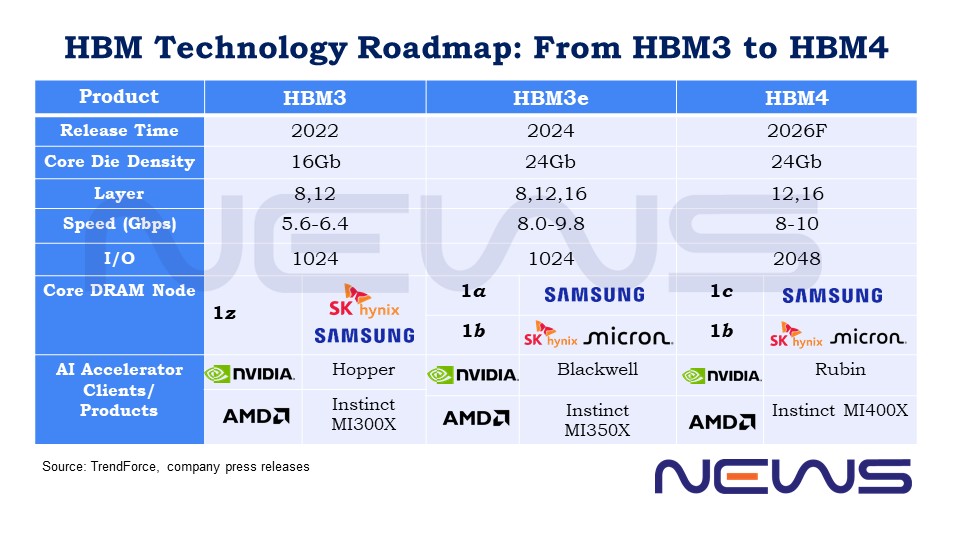

With the HBM4 era on the horizon and SK hynix and Micron preparing for production ramp-up from late 2025 through 2026, it is an ideal time to explore how HBM (High Bandwidth Memory) is built, its key advantages and technologies related, and why its manufacturing complexity drives high costs. Here’s a quick roundup of the essential points.

Inside HBM: Composition and Key Benefits

As AI models grow more sophisticated—handling both intensive training and real-time inference—they demand memory that can deliver on three fronts: size, speed, and efficiency. While SRAM excels in speed but falls short on capacity, traditional DRAM offers ample storage but lacks sufficient bandwidth. HBM emerges as the sweet spot, offering an optimal balance between capacity and speed.

HBM achieves this through its unique stacked architecture: multiple DRAM dies built atop a logic (base) die, connected via thousands of parallel interconnects. This entire stack links to an xPU through a silicon interposer on the package substrate, typically paired with GPUs such as NVIDIA’s.

This architecture delivers several key advantages. First, energy efficiency: the close integration between HBM and xPU keeps data paths short, reducing power consumption. Second, massive throughput.

In comparison, HBM4 typically uses 40–50% less power than DDR4 to achieve the same bandwidth. While a DDR4 module maxes out at around 25.6 GB/s, a single HBM4 stack delivers over 1 TB/s of bandwidth—an enormous boost that is essential for workloads demanding rapid access to massive datasets.

Breaking the Memory Wall: Why HBM Powers the AI Era

In the generative AI era, training a model at the scale of ChatGPT usually requires tens of thousands of GPUs working simultaneously. However, while GPU computing power has increased 60,000-fold over the past 20 years, DRAM memory bandwidth has improved by only 100-fold—creating what’s known as the “memory wall.” Put simply, no matter how fast the GPU processes, it gets bottlenecked if memory cannot supply data quickly enough.

HBM, with its vertical stacking structure, was developed precisely to break through this barrier. It is like a skyscraper, with layers of DRAM chips stacked one on top of another. Technically, each DRAM die is roughly 30–50 µm thick, connected to the underlying logic base through through-silicon vias (TSVs) and microbumps, and finally linked to the GPU via a silicon interposer.

This architecture enables HBM to transmit data through thousands of “high-speed channels” simultaneously, delivering bandwidth far beyond that of traditional DDR memory.

The Price of Innovation: HBM’s Engineering Challenges

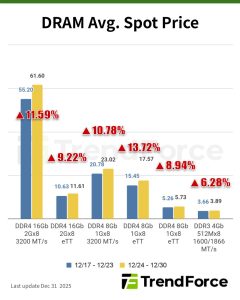

However, building a skyscraper like this is highly costly. According to TrendForce, HBM3e already launched with an estimated 20% price premium, and HBM4’s added complexity is expected to push that premium beyond 30%.

The higher cost, TrendForce notes, comes from HBM4’s more intricate chip design, which enlarges the die size to accommodate a significant increase in I/O count. In addition, some manufacturers are shifting to a logic-based base die architecture to further enhance performance, with both factors contributing to steeper production costs.

Notably, stacking complexity continues to be a major hurdle with each new HBM generation. As layers increase to 12 or even 16, the yield of TSVs becomes a critical bottleneck.

To address these challenges, different manufacturers have adopted varying approaches. SK hynix has taken the lead by leveraging its MR-MUF (Mass Reflow Molded Underfill) technology, while Samsung and Micron continue to rely on the TC-NCF (Thermal Compression with Non-Conductive Film) method.

According to SK hynix, applied to the company’s HBM2 products since 2019, MR-MUF has set the company aside from the competition. This tech works like a “two-in-one” process, combining chip connection and protective filling in a single step. While the traditional approach is like building a house first and patching cracks afterward, MR-MUF is more like sealing cracks as you build—faster, sturdier, and far less prone to issues.

In simple terms, mass reflow melts the bumps between stacked chips to connect them, while molded underfill fills the gaps with a protective material that boosts durability and helps dissipate heat. This combined approach is especially effective for high-layer, high-bandwidth applications with demanding thermal requirements—like HBM.

Compared to NCF, MR-MUF offers roughly twice the thermal conductivity, which has a significant impact on both production speed and yield.

However, hybrid bonding—by directly connecting chips without bumps—enables thinner stacks, more layers, reduced signal loss, and better yields. Thus, major HBM manufacturers are considering whether to adopt hybrid bonding for HBM4 16hi stack products but have confirmed plans to implement this technology in the HBM5 20hi stack generation.

HBM4 Base Die: Why Memory Makers Turn to Foundries

Nonetheless, stacking DRAM layers is just the start; the next challenge is building them atop a highly precise, deep foundation, much like engineering a skyscraper.

This is extremely important in the HBM4 era, as the product needs a specialized foundation called the logic die. This foundation, strikingly, must handle over 2,000 precise connection points (from 1,024 to 2,048 I/O counts) – imagine a building requiring 2,000 individual utility lines – with interconnect spacing of just 6-9 micrometers, roughly 100 times thinner than human hair.

Traditional memory makers, accustomed to building ‘residential homes’ (standard memory), suddenly face the near-impossible task of constructing these ultra-deep skyscraper foundations. As buying billions in ultra-precision excavation equipment just to occasionally dig such foundations simply isn’t financially viable, they turn to foundries with expertise, just like TSMC.

Take TSMC as an example. As noted by TechNews, the foundry giant possess the most advanced tools (N5 and N12FFC+ processes), as its N12FFC+ process enables construction of 12-stack (48GB) or 16-stack (64GB) memory “buildings” with data transfer speeds exceeding 2TB/s – like installing super-speed elevators. On the other hand, their N5 process offers even more precision with 6-9 micrometer spacing, enabling direct bonding technology that allows memory stacks to be built directly atop logic chips.

HBM: Still an Oligopoly Game

As memory giants gear up for the HBM4 era, racing to secure NVIDIA verification, one thing is clear: the high manufacturing complexity keeps HBM firmly in the hands of a few key players. TrendForce projects SK hynix to lead with 59% of shipments in 2025, while Samsung and Micron will each hold about 20%.

In the upcoming HBM4 battleground, NVIDIA and AMD remain the heavyweights, driving demand for memory giants. NVIDIA unveiled its next-generation Rubin GPU at this year’s GTC, while AMD is preparing its MI400 series as a direct competitor—both expected to feature HBM4.

On the specification side, each DRAM die in HBM typically measures 30–50 µm thick, with stacks commonly built from 4, 8, or 12 dies. JEDEC has confirmed a relaxed nominal package thickness of 775 µm for both 12-high and 16-high HBM4 stacks, up from 720 µm for HBM3.

On the other hand, HBM4 doubles the I/O count from 1,024 to 2,048 compared to previous generations, while maintaining a data transfer rate above 8.0 Gbps—on par with HBM3e. This implies that HBM4 can deliver twice the data throughput at the same speed, thanks to its increased channel count.

With the logic die at the center of collaboration, foundries like TSMC are playing an increasingly critical role—teaming up with SK hynix on HBM4 and Micron on HBM4E—making the HBM4 battleground more dynamic and unpredictable than ever.

(Photo credit: SK hynix)